Imagine it’s tax filing season. You’re dreading figuring out your tax liability this year, because in the last few years you’ve been earning sporadic capital gains and dividends that sometimes have led to a surprise tax bill at year-end. This year, though, is the first year that pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) tax collection has been expanded beyond wage income to cover additional types of earnings, causing your capital gains and dividends to be withheld at source, as well as some key deductions and credits, so that you don’t have to retrospectively reconcile your income, withholding, and deductions—all you need to do is fill out and file your Form 1040. There is no big bill, because withholding at source was applied on all of your income, and because it accounted in advance for the standard deduction and for the deduction you knew you would claim for student loan interest.

This hypothetical scenario is a reality in some other countries, such as the U.K., which have embraced advances in technology to improve the accuracy and breadth of their tax withholding systems. For example, the U.K. utilizes real-time reporting technology to exchange information with employers and has made a variety of changes in its tax system, in part to more effectively facilitate its expanded PAYE system. Among other things, the U.K. relies on a single unit of taxation (the individual), doesn’t tax capital gains and dividends below a certain threshold, and administers certain entitlement programs outside of the tax system. These structural adjustments enable two-thirds of U.K taxpayers to fully and accurately satisfy their tax liabilities by year-end.

Other countries, including New Zealand, Spain, Australia, and France, have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, similar approaches to provide a more expansive, user-friendly tax system. While they differ in scope and particulars, they are similar in that, insofar as possible, they seek the broadest PAYE coverage for the greatest number of taxpayers. Additionally, the U.K. has made strides toward a return-free filing option, under which taxpayers who neither owe nor are owed payments at year-end are allowed to forego the formality of filing a tax return. Other countries also may incorporate return-free filing as the breadth and accuracy of their PAYE systems make this option feasible.

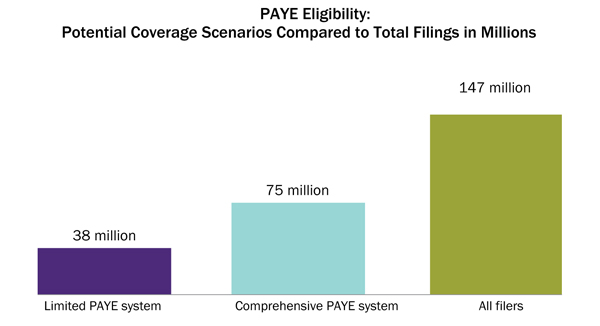

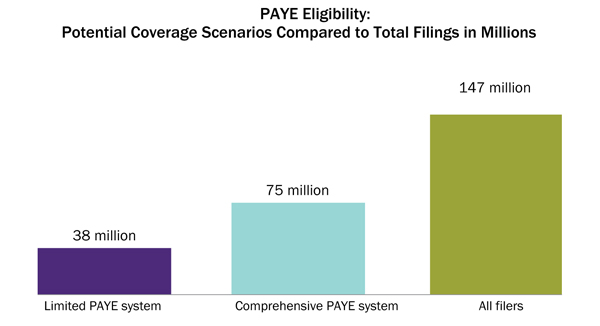

Whether or not the U.S. would want to take such steps and would be willing to implement changes to the tax system such that a comprehensive PAYE system would be possible remain open questions. Nevertheless, the potential benefits flowing from an expanded PAYE system prompted TAS to examine what other countries are doing in this area and to analyze how such a system might be applied in the U.S. A link to our study is here. For example, we determined that a PAYE system that withheld taxes from the four most common types of income (wages, interest, pensions, and dividends) and that accommodated the standard deduction would allow accurate PAYE coverage for 26 percent of U.S. tax returns (38 million). If that system were expanded to cover seven of the common types of income and the seven most common deductions and credits, it would cover 51 percent of tax returns (75 million), as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 1. PAYE Eligibility: Potential Coverage Scenarios Compared to Total Filings in Millions

The seven common income types we considered are wages, interest, taxable pensions and annuities, ordinary dividends, capital gains, Individual Retirement Account (IRA) distributions, and unemployment. Of the 147 million tax returns filed for tax year (TY) 2016, 62 percent reported only income fully captured by seven line items on IRS Form 1040 as shown on the table below.

Figure 2. Cumulative Buildup of PAYE Income Items, TY 2016 Returns

The seven most common deductions and credits are the standard deduction, the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, the student loan interest deduction, the child and dependent care expenses credit, the IRA deduction, and the health savings account deduction. These deductions and credits based on tax returns filed in TY 2016 are set forth in the table below.

Figure 3. Deductions, Credits, and Potential PAYE Coverage, TY 2016 Returns

Although more easily said than done, imposing withholding at source on the seven income items would require only an additional conceptual step in tax administration, as payors are already required to provide the IRS with information reporting on these items. On the other hand, incorporating deductions and credits into a comprehensive PAYE system would be more complex and likely would require some of the same adjustments made to the U.K. system, such as adoption of the individual as the unit of taxation and administration of provisions relating to family size and structure outside of the tax system.

Along with potential structural alterations to the tax system, expanded PAYE coverage would also result in a reallocation of burdens. For example, payors who currently only are required to fulfill information reporting responsibilities would also need to undertake withholding at source on a variety of income items. Such a change in the basic structure of tax administration initially would be costly and time-consuming for payors. Further, taxpayers would be required to disclose additional amounts of potentially sensitive personal information to their employers (see next week’s blog for a potential solution to this privacy concern). These downsides should be carefully considered before moving forward with any such changes. Moreover, the requisite systemic alterations may or may not ultimately be acceptable to taxpayers, stakeholders, and policymakers.

Nevertheless, substantial upsides present themselves as well. An increase in PAYE coverage, be it of modest or more ambitious scope, would yield benefits to both taxpayers and the government.The more income items included in a PAYE regime, the more taxpayers would have their tax liabilities fully collected at source. This circumstance would free many taxpayers from the potential of paying large year-end tax liabilities and would free the IRS from having to seek payment of those liabilities from taxpayers, some of whom may have already spent the money on living and other expenses. An expanded PAYE system would also substantially minimize the number and impact of reporting errors made by good-faith taxpayers, as many of the calculation and remittance duties would be undertaken by employers or other third parties.

Likewise, the IRS would collect tax revenues more quickly and easily than is currently the case. Further, because information reporting and tax collection would be occurring via third parties, opportunities for noncompliance and fraud would be reduced. Given these and other benefits, in TAS’s introductory study recently published in the Annual Report to Congress, I have recommended that the IRS, Treasury, and TAS collaborate on an in-depth follow-up study analyzing the steps that would need to be undertaken, the challenges that would need to be overcome, and the trade-offs that would need to be accepted in order to make an expanded PAYE system feasible in the U.S. In order to keep our approach to tax administration from growing stagnant, it is crucial that we think creatively, examine strategies that have been embraced in other countries, and consider innovations that could improve the quality of tax administration for both taxpayers and the IRS.