Subscribe to the NTA’s Blog and receive updates on the latest blog posts from National Taxpayer Advocate Erin M. Collins. Additional blogs can be found at dev.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/blog.

With the onset of 2015, I made a New Year’s resolution to restart my blog and provide periodic insights and observations on U.S. tax administration. The New Year also coincides with the issuance of my Annual Report to Congress. Selecting 20 of the most serious problems of taxpayers for this report is always a challenge, because there are so many things to write about. Each year I establish a theme for the report, which provides a framework for selecting the problems but can exclude many important issues. The blog can help bring some focus on these issues and the work that the Taxpayer Advocate Service (TAS) and others are undertaking in those areas.

My collection advisors and I spend a lot of time dealing with collection issues and analyzing collection data. It is fitting, then, that my first blog of the New Year takes a closer look at the IRS’s collection performance.

The Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 (RRA 98) provided the IRS Collection operation with a mandate to improve service for taxpayers, and reduce its reliance on liens, levies, and seizures to collect tax debts.

The IRS Collection operation was the subject of considerable attention in the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 (RRA 98). Key components of the legislation were designed to enable the IRS to more effectively use collection payment options, such as installment agreements (IAs) and offers in compromise (OICs), to enhance taxpayer compliance, and make it easier for taxpayers to enter into these types of alternative payment arrangements. In regard to OICs, Congress expressed an interest in having the IRS adopt a “liberal acceptance policy” in order to “provide an incentive for taxpayers to continue to file tax returns and continue to pay their taxes.”(1) In developing the legislation, Congress was clear in its stated belief that “the ability to compromise tax liability and to make payments of tax liability by installment enhances taxpayer compliance.”(2)

Conversely, RRA 98 also addressed reported abuses by the IRS pertaining to the use of its formidable collection enforcement tools, specifically liens, levies, and seizures. The IRS differs from other creditors because it possesses the ability to undertake significant collection actions without the necessity of going to court and seeking a judgment. In the development of RRA 98, Congress expressed the belief that “the imposition of liens, levies, and seizures may impose significant hardships for taxpayers.” (3) Consequently, RRA 98 contained a number of new provisions designed to limit the use of these tools in certain situations, as well as new review and approval requirements for liens and levies. RRA 98 also created new avenues for taxpayers to appeal IRS enforcement actions, most notably through Collection Due Process (CDP) hearings.

The implementation of RRA 98 proved to be a challenge for the IRS, and most notably for the Collection operation. In retrospect, much more attention was afforded to declines in the numbers of IRS enforcement actions than was given to efforts to improve revenue collection and compliance through the expanded availability of payment options. In its May 2002 report, the United States General Accounting Office – now known as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) – commented on the IRS’s decreasing use of enforcement sanctions, noting that the number of liens, levies, and seizures “dropped precipitously” between fiscal years (FY) 1996 and 2000. (4) A commonly held perception following the implementation of RRA 98 was that the reductions in liens, levies, and seizures reflected a general decline in IRS enforcement, particularly with respect to the IRS Collection operation, and that the IRS’s new emphasis on taxpayer service was incompatible with a robust collection program. In fact, later discussions of collection program results commonly compared lien and levy activity with pre-RRA 98 levels, and increased activities in these enforcement areas were cited as improvements in IRS performance. (5)

IRS data reveal a very weak correlation between the raw numbers of collection enforcement actions and the collection of delinquent tax dollars.

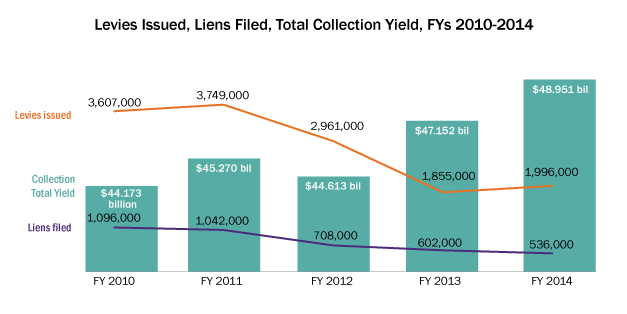

As illustrated in the chart below, IRS data reveal that the substantial reductions in liens and levies that the IRS experienced post-RRA 98 had no discernible impact on the collection of delinquent revenue during this period. (6) IRS defines the term “Total Collection Yield” to include dollars collected on unpaid assessments in the notice stream, collections from taxpayer delinquent accounts (“TDAs”, i.e., cases assigned to or awaiting assignment to Collection personnel), installment agreements, deferred accounts, and non-master file accounts. (7)

Unfortunately, the IRS’s preoccupation with the volumes of lien and levy actions hampered efforts to identify the collection treatments that successfully delivered this revenue with the aid of improved taxpayer service, e.g., timely personal contacts and more flexibility in the use of payment options such as installment agreements and offers in compromise.

In FY 2015, the IRS Collection operation faces an environment that is in many ways remarkably similar to the years following the implementation of RRA 98. Severe budget cuts have contributed to reductions in Collection staffing. From the end of FY 2010 to the end of FY 2014, ACS permanent staffing has declined by over 31% and revenue officer staffing has declined by over 27%. (8) Moreover, significant changes in IRS collection policies implemented in FY 2011 and 2012, i.e., the so-called IRS “Fresh Start Initiative,” have placed greater emphasis on more flexible collection decisions, as opposed to increased use of traditional enforcement actions. As a result, from FY 2010 to 2014, levies issued by the IRS decreased by 45%, (9) and lien filings decreased by 51%. (10) Remarkably, Total Collection Yield increased by 14% in nominal dollars during this period, despite the dramatic decreases in traditional enforcement actions. (11)

Even more remarkably, inflation-adjusted Total Collection Yield increased by 1.7% between FYs 2010 and 2014, demonstrating that collection revenue has been relatively stable over time despite significant swings in IRS lien and levy activity. (12)

As illustrated in the chart below, revenue collected through installment agreements and collection notices was the primary driver for the increase in Total Collection Yield, with increased collections through refund offsets also making some contributions. Notably, collection through initial IRS collection notices is voluntary – albeit late – compliance (i.e., no lien or levy prompted the taxpayer’s payment), and collection by refund offsets is a fully automated approach that does not require IRS lien or levy authority.

One might attribute the increase in Total Collection Yield to the overall increase in taxpayers. Between FY 2010 and FY 2014, the number of individual taxpayers increased by about 5%, while the number of business taxpayers remained stable. IRS data, however, disproves this assumption. As the chart below shows, the TDA dollars available for collection decreased slightly between FYs 2010 and 2014, from $174 billion to $173 billion. (13) At the same time, the number of liens issued decreased by about 50%, from almost 1.1 million to 536,000. Yet the percentage of dollars available for collection that were actually collected increased from 6.0% to 6.4%. The chart below shows even more dramatically the relationship between liens filed and available dollars collected.

We see the same pattern with levies issued. Specifically, the number of levies declined by 45% from FY 2010 to FY 2014, while the percentage of available dollars collected decreased slightly.

Now, there are many factors that influence Total Collection Yield. But these data certainly indicate that something other than the raw number of lien and levy issuances accounts for the relative stability of collection revenue over time. In my next blog, I’ll explore what that “something” might be.